In the European and Mediterranean traditions, the year has a ritual beginning and a ritual ending, corresponding with two different moments of the seasonal and astronomical cycle: the Spring Equinox, when nature is reborn, and the Winter Solstice, when the rebirth of the solar cycle begins.

For a long time, nature’s new year in spring remained connected with agriculture, celebrated with propitiatory rites and giving thank for the newly found fertility, while the astronomical new year, in winter, gained the symbolic meaning of threshold between the physical and the spiritual world, between light and dark, resulting in rites that represent opening and closure.

Dates and rites of these ancient celebrations changed – even geographically – as did different cultures, but as different cultures met, so did their traditions. An example of this is the calendar of Western Christian traditional celebrations: the Winter Solstice is celebrated with rites that range from early November to January, and some extend to February, in a cycle that celebrates its different symbolic aspects.

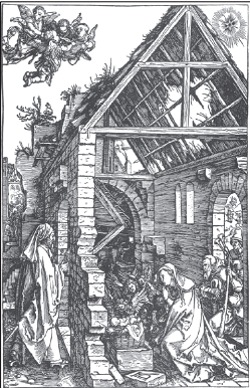

Christian nativity scene, XIV Century engraving

The traditional cycle of festivities

In Trieste, this traditional cycle begins in November with the celebration of all saints and with the commemoration of all the deceased, which symbolize, on pre-Christian roots, the opening of the threshold with the otherworld and the communication between the two worlds, which is celebrated with rites of honor and remembrance, including the gifting of flowers or food (for example, Trieste offers traditional sweets “fave”) dedicated to the souls on the other side, and lighting small candles to represent the connection with the world of light.

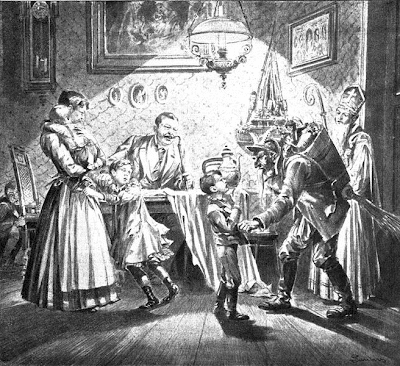

Follows December 6th, and the celebration of two lesser spiritual beings, representing good and evil respectively: they come from the otherworld with warnings about the past year’s credits and faults, rewarding the former and punishing the latter.

In Mitteleuropa, the two spirits are represented as St. Nikolaus and the devil Krampus traveling together on a journey during which those at fault can repent begging for forgiveness. In certain places, this tradition intertwines with the very ancient masquerade of Nature’s spirits, wrapped in skins, hay, horns, branches, and bells, who appear also at other moments of the Solstice celebrations.

On December 25th, Western Christians celebrate Christmas, the symbolic rebirth of divine light in the World for the sake and redemption of all, especially the humble and persecuted, and once this was also a symbolic day to give children small gifts.

Saint Francis of Assisi, mystic of simplicity and creation, assembled the nativity scene to represent it, while the lore of Mitteleuropa added fir trees, a pre-Christian symbols of vital force thanks to their leaves remaining green also in wintertime.

This is the three celebrations that convey the holy aspects of Solstice celebrations; the calendar’s New Year’s Eve, December 31st, is a secular, merry celebration, and in Mitteleuropa it has its own vital symbol: fir mistletoe, not only because it stays green like the tree, but because of its small light berries.

For Western Christians, the traditional cycle ends on January 6th with the Epiphany, a symbol of the recognition, by three wise men (Magi, màgoi) that a Star (symbol of cosmic harmonies) guided from the East to the manifestation(epiphanéia) of God’s love (charitas) on Earth as universal law. The celebration is often accompanied by children who impersonate the three Magi on a plea as a good omen.

In Mitteleuropa it is a new year tradition tracing on the entrance of buildings the protective initials of the three Magi’s given names: C.M.B. (Caspar, Melchior, Balthasar) and formula Christus Mansionem Benedicat (May Christ bless this house) accompanied by cross signs.

One last echo of the Winter Solstice celebrations occurs in February and March, before the beginning of the Spring cycle and of Western Christian Easter: certain ancient forms of Carnival celebrations. This feast mixes together many different traditions, for example, the masquerade of Nature’s spirits, associated to a momentary suspension even a subversion of social norms, and formerly a representation of the Solstice-time sudden connection with the Otherworld (featured also in certain very ancient mystery cults).

Modern, consumeristic trivializations

Traditional celebrations of the Winter solstice are, like others celebrations on the autumn cycle, a precious cultural and spiritual heritage, because they renew, also with Christian symbols, the perception of holiness, which is as old as humanity, connected to changing season. This is a deep, essential sensitivity, the weakening of which has disastrous consequences for our inner life and also on our external actions on the natural environment and on other lifeforms.

Consumeristic trivializations of those holidays are, therefore, more than mere amusing, funny, and harmless games, because they suffocate those spiritual meanings and values in a vortex of barren, materialistic urges, and connect them with commercial pseudo-traditions thus spreading such anti-values even among children.

The most harmful of such pseudo-traditions is that of Santa Claus (Babbo Natale in Italian), a commercial invention that is suffocating the spiritual atmospheres and meanings of Christian Christmas with a consumeristic masquerade exasperated and grotesque.

That is a very recent figure, originated in the US by superimposing the traditions of Saint Nicholas and the Christmas Tree of immigrants from Mitteleuropa with Ded Morož (Grandpa of Father Frost, a winter spirit) of Russian and other Eastern European immigrants with the Anglo-Saxon and Northern European traditions about gnomes and elves and with the commercial logics of profit.

This mixture results in a sort of childish neopagan cult of consume and gifts, which, after WWII, was spread with Walt Disney comics and Coca Cola commercials allover the World, except in the Central and Eastern European communist States, where there are, instead, parallel versions akin to Russia’s Ded Morož in order to substitute the Christian Christmas and make New Year a gift-giving holiday.

The end of communism has not always meant the return of traditional Christmas, rather, a global victory of the opposite US tradition, in a wild orgy of gifts, waste, and more consumerism. The global spreading of this consumeristic version of Christmas is also in conflict with non-Christian traditions, especially those of Muslims, Jews, and Buddhists.

There is also another, more recent pseudo-tradition, more problematic than it seems: it is the consumeristic spreading of Halloween, which from North America has trivialized and spread around the world ancient Celtic traditions connected with the celebrative cults of the spirits and of the dead once held during the Solstice. That ancient tradition is downgraded to a horrid masquerade of children and adults and, under the guise of a folkloristic game, spreads a message that is essentially of indifference to evil (which adds a layer to the permanent, suggestive thread of spectacles of horror and violence accessible also to children).

There is one more, typical Italian trivializations – spread as such by the Fascist regime – and it is the one superimposing to the meaning of the Christian epiphany, to the point of taking its very name away, the character of the gift-giving “Befana”.

The character herself derives from an Italian regional variation (from the Apennines) of a female winter spirit that is herself a picture of traditions: Celtic and Germanic culture on one side (Holda-Berchta) and Slav on the other (Zima-staruha); the character is represented as the people used to imagine witches, and she became just another commercial pseudo-tradition.

To European traditional celebrations of the New Year are now superimposed secular, consumeristic variations which exasperate the ancient Chinese rite of firecrackers and fireworks to drive away the past year’s demons.

All while the traditional Carnival, spontaneous, agricultural, and connected to very ancient local traditions, was trivialized and commercialized, losing its local peculiarities to world-wide models that are themselves consumeristic, trivial ostentation, and political satire.

This confirms the opportuneness of taking the time to think about such consumeristic traps and to understand if it’s worth continuing to be suffocated by them. Maybe it’s better returning to the essence and to the atmosphere of our traditional ethnic and religious, authentic, sober Winter celebrations.

Many of us preserve eternal memories of those festivities, and even the most secular and loud, as New Year celebrations are, can become deeper, for example, if that night is spent in the woods, near grasslands or the waters, or in any other fragment of this world of ours under the infinite starry sky.

Author of the English version: Silvia Verdoljak.